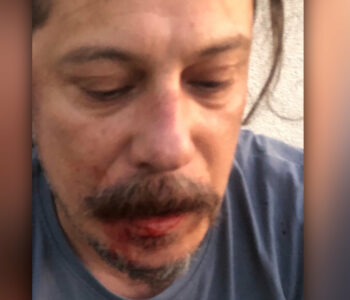

Already in 2020, reported attacks against journalists had more than doubled compared to the previous year. This dramatic increase to 255 aggressions can be attributed to the regular demonstrations taking place across Germany against government Covid-19 measures, including planned mandatory vaccination. According to MFRR data, right-wing extremist rallies are also particularly hostile environments for media professionals.

From January 1 until December 15, 2021, the MFRR recorded 108 violations to press and media freedom in Germany, with 85 of these violations taking place as attacks against journalists during demonstrations. Yet, the real figure is expected to be much higher: due to safety reasons, many journalists choose not to go public when they receive threats. A common misperception is also that attacks, particularly online harassment, are simply “part of the job”. The MFRR aims to reverse such attitudes and joins the German Journalists Association (DJV) in urging journalists and media professionals to press charges, should they receive threats or be subjected to other kinds of violence.

During demonstrations, journalists are frequently physically attacked, their equipment is targeted and insults and threats are also common. Freelance photojournalist Aaron Karasek, who has been subjected to repeated violence during protests, shared on Twitter: “At this point, there are almost no Querdenker demonstrations where I or colleagues do not get attacked.” Due to such experiences, TV crews from large broadcasters now usually go to Querdenker demonstrations with security guards. While this might create a feeling of safety, it does not always prevent journalists from being attacked, as for instance the aggression against an SWR TV team accompanied by three security staff shows. Further, a lack of resources does not allow all journalists to make use of such support.

Against this backdrop, we have repeatedly called for better police response and training in order to guarantee the safety of journalists. However, as recent protests – such as in Dresden – have shown, police officers even obstruct journalists in their work when they should be protecting them. The MFRR has recorded physical attacks, threats, confiscation of materials, reporting restrictions and detentions against journalists and media professionals. In 26 alerts on the Mapping Media Freedom (MMF) platform in 2021, police or state security were reported as the sources of attacks. This attitude targeting members of the media is unacceptable and the MFRR stresses the need to actively support press and media freedom.

The German Journalists Union (dju in ver.di) and the German Journalists’ Association (DJV) have repeatedly demanded to increase the number of police officers at demonstrations to better focus on the needs of journalists. The Federal Ministry of Interior indicated that safety procedures will be improved. Right now, the police are often highly understaffed and overwhelmed. While they frequently set up separate areas for media workers to be shielded from aggressions, journalists criticise that such zones separate them from the demonstrations. Strategic de-escalation and unhindered press work, in contrast to reported tedious press card checks and journalists’ expulsions, are desirable.

Another major problem, that often goes hand in hand with anti-Covid-measures demonstrations, is the use of online messaging application Telegram, to plan attacks and exchange information about journalists. The police should do everything in their power to punish these unacceptable acts and application managers should take reports of plans of violence on their platforms seriously and manage the groups according to their community standards. While it is difficult to regulate Telegram, keyword Network Enforcement Act, investigative authorities still have options to counter the spread of calls for violence there. Threatening cases on online platforms involving journalists should be prioritised.

While the amount of attacks against journalists in Germany is particularly alarming, it should also be noted that aggressions during demonstrations and threats via Telegram channels are on the rise in various European countries, such as in France, Italy, the Netherlands or Luxembourg. The MFRR is closely monitoring these violations and calls on the governments and police to take preventive measures and to thoroughly investigate these attacks.

Good practice examples to better promote a safer environment for journalists are listed below:

- In the Netherlands, the police and the public prosecutor’s office give priority to incidents concerning journalists. Following an agreement in 2018, concrete guidelines and training have been offered to law-enforcement services to better respond to threats against the media. A hotline enabling journalists to report acts of aggression has been set up.

- In the UK, the government has adopted a national action plan to protect journalists from abuse and harassment. Every police force is to deal with a designated journalist safety liaison officer, and at national level a senior police officer will take responsibility for crime against journalists at national level.

- In Sweden, the government has commissioned the Swedish Crime Victim Compensation and Support Authority to produce a training and information resource on support for journalists exposed to threats. The government has also commissioned Linnæus University to build a knowledge centre and a OBCservice offering advice and support to journalists and editorial offices, including freelancers, small offices and smaller production companies.

Event

Event