Allgemein

Allgemein

Hungary: Media Capture Monitoring Report 2025

Hungary: Media Capture Monitoring Report 2025

The International Press Institute (IPI) and the Media and Journalism Research Center (MJRC) today jointly launch a new series of Media Capture Monitoring Reports for 2025, with Hungary the first country report to be published.

12.11.2025

The new report reviews developments regarding media capture in the country in 2025 and examines Hungary’s compliance with the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA) since the EU Commission’s regulation entered into full force in August.

It concludes that Hungary remains the EU Member State with the most sophisticated model of media capture ever developed within the bloc, and that rather than take any steps to implement the EMFA, the Hungarian government has framed it as a tool of foreign interference and legally challenged the regulation before the European Court of Justice seeking to have elements annulled.

Ahead of the April 2026 election, the report explores the opportunities and challenges posed by the EMFA for improving Hungary’s media environment, including strengthening regulatory independence and public service media governance, increasing ownership transparency, strengthening safeguards for media pluralism and guaranteeing the fair distribution of state funds.

It also provides detailed recommendations on a variety of measures and policies necessary to unwind entrenched media capture in Hungary and create a free, pluralistic and democratic media ecosystem, in line with EMFA provisions.

This report is part of a broader series covering seven other EU countries: Bulgaria, Finland, Greece, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Spain. IPI and MJRC will also publish an overview report, summarising major developments across the EU in the past year. The next reports will be published over the following weeks.

These reports are intended as a vital resource for media rights organizations, civil society groups, policymakers, and advocates dedicated to monitoring and fostering media freedom across the EU.

For more information or media inquiries, please contact:

- Jamie Wiseman, Senior Europe Advocacy Officer – IPI, jwiseman@ipi.media

- Marius Dragomir, Project Editor – MJRC, mdragomir@journalismresearch.org

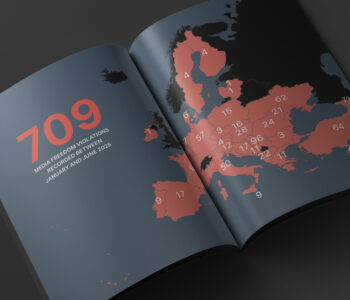

This report was coordinated by IPI as part of the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries.