In Memory of Daphne: Media reform public consultations must…

In Memory of Daphne: Media reform public consultations must lead to National Action Plan

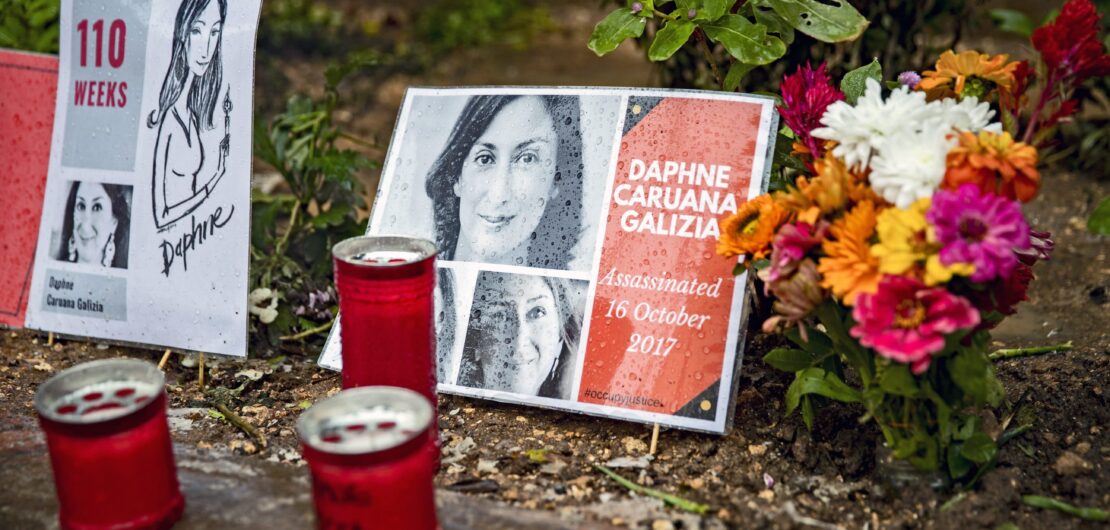

On the eve of the anniversary of the murder of Maltese investigative journalist Daphne Caruana Galizia, press freedom and journalists’ groups are calling on the national authorities to set up a National Action Plan on Media Freedom and Journalist Safety.

15.10.2025

Our groups reiterate our calls for all perpetrators of the murder to be brought to justice and we continue to monitor the progress of ongoing legal proceedings.

- Overview:

Press freedom and journalist organizations welcome the call by the Maltese authorities for public consultations on media freedom and are, in this paper, submitting a set of recommendations for consideration.

The implementation of such recommendations would be an appropriate and meaningful way to continue to mark the life and legacy of Daphne Caruana Galizia, who was killed in a car bomb attack on 16 October 2017.

The move to open up public consultations follows an ongoing exchange on institutional and rule of law reforms in Malta, whose record has been the subject of international scrutiny since the journalist’s murder eight years ago.

Such reforms present a historic opportunity for press freedom in both Malta and Europe. Press freedom and journalists’ groups call for draft legislation related to reforms to be considered for consultation, including by national and international civil society, journalists’ organizations, media freedom experts, the Council of Europe, and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), prior to being enacted by parliament or published by legal notice.

Our organizations are tracking the reform proposal put forward by the Maltese authorities in

response to the European Media Freedom Act (EMFA). Some recommendations below identify areas of concern that continue to require a more effective state response than outlined in the August 2025 legal notice.

This statement seeks to provide an overview of key international standards or texts that would provide a basis for shaping the planning and implementation of future legislative and non-legislative measures to protect journalists. It also provides a list of recommendations, in consideration of Malta’s press freedom context.

Such reforms should be brought together in a National Action Plan on Media Freedom and Journalist Safety. Such an initiative should seek to concretely address the complex set of challenges facing all Maltese journalists, and guarantee an ambitious vision for Malta’s compliance with its European Union, Council of Europe and OSCE obligations.

- Relevant international standards and expert sources:

The following international standards and texts provide guidance on the questions raised in the consultation, including safeguarding an enabling environment for journalists to operate, preserving full and independent access to information, and aligning all measures with international standards on the protection of the reputation or rights of others.

United Nations

– Civil and Political Rights, including the Question of Freedom of Expression, the right to freedom of opinion and expression, Report of the Special Rapporteur, Ambeyi Ligabo, 30 December 2005 (E/CN.4/2006/55)

– General Comment No. 34, Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression, United Nations, Human Rights Committee, 11-29 July 2011 (CCPR/C/GC/34)

– General Assembly, Resolution 68/163, The Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity, 18 December 2013 (A/RES/68/163)

– General Assembly, Resolution 39/6, The Safety of Journalists, Human Rights Council

27 September 2018 (39th Session) (A/HRC/RES/39/6)

UNESCO, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation

– UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity (2012)

Council of Europe, Parliamentary Assembly

– Parliamentary Assembly, Recommendation 1506 (2001), Freedom of expression and information in the media in Europe, Council of Europe, 24 April 2001

– Parliamentary Assembly, Recommendation 1589 (2003), Freedom of expression in the

media in Europe, Council of Europe, 28 January 2003

– Parliamentary Assembly, Resolution 1535 (2007), Threats to the lives and freedom of expression of journalists, 25 January 2007

– Parliamentary Assembly, Resolution 2035 (2015), Protection of the safety of journalists and of media freedom in Europe, 29 January 2015

– Parliamentary Assembly, Recommendation 2062 (2015), Protection of the safety of journalists and of media freedom in Europe, Council of Europe, 29 January 2015

– Parliamentary Assembly, Resolution 2317 (2020), Threats to media freedom and journalists’ security in Europe, Council of Europe, 28 January 2020

Council of Europe, Committee of Ministers

– CM/Rec(2024)2 – Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to member States on countering the use of strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs), adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 5 April 2024

– CM/Rec(2022)16 – Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to member States on combating hate speech, adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 20 May 2022

– CM/Rec(2016)4 – Recommendation of the Committee of Ministers to member States on the protection of journalism and safety of journalists and other media actors, adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 13 April 2016

European Court of Human Rights case-law on state interference or restriction on freedom of expression:

Stoll v. Switzerland, App No 69698/01, (ECtHR [GC] 10 December 2007)

Morice v. France, App. No. 29369/10, (ECtHR [GC] 23 April 2015)

Pentikäinen v. Finland, App No 11882/10, (ECtHR [GC] 20 October 2015)

Khadja Ismayilova v. Azerbaijan, App Nos 65286/13 and 57270/14, (ECtHR 10 January 2019)

Yılmaz and Kılıç v. Turkey, App No 68514/01, (ECtHR 17 July 2008)

Bahçeci and Turan v. Turkey, App. No. 33340/03, (ECtHR 16 June 2009) para 26.

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, OSCE

Legal analysis on the draft law of Malta to implement various measures for the protection of the media and of journalists, October 2021

Legal analysis on the draft law of Malta to implement various measures for the protection of the media and of journalists, February 2022

European Commission

Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/1534 of 16 September 2021 on ensuring the protection, safety and empowerment of journalists and other media professionals in the European Union

Commission Recommendation (EU) 2022/758 of 27 April 2022 on protecting journalists and human rights defenders who engage in public participation from manifestly unfounded or abusive court proceedings (“Strategic lawsuits against public participation”)

Commission Recommendation (EU) 2022/1634 of 16 September 2022 on internal safeguards for editorial independence and ownership transparency in the media sector

- Recommendations

- Establish a National Action Plan

– In line with the Council of Europe’s “Journalists Matter” campaign, develop and adopt a National Action Plan on Media Freedom and Journalist Safety to provide a strategic framework to coordinate action across all state institutions. Such an action plan should integrate the recommendations listed below (to the fullest extent possible), and should follow further broad, public and transparent consultations, timeframes, clear and measurable benchmarks for progress, and effective and independent evaluation processes. It would have full political backing; would be led by a person or persons with experience and knowledge of the media (and the threats to the media); and would have the full trust of the journalist community and their representative organizations.

- Set up an institutional response structure

– Establish an interministerial, cross-institutional structure for the protection of journalists and journalism, with a view to implementing the National Action Plan, setting up rapid response protocols and early warning mechanisms, regular communication and dialogue on press freedom concerns affecting Malta’s journalists, and building state accountability for protecting journalists. Such a structure should ensure effective engagement with civil society and media organizations, and have, as its purpose, the full implementation of the 2016 Committee of Ministers Recommendation on journalism safety and the European Commission’s 2021 Journalist Safety Recommendation. This requires that the current mechanism be transformed to meet international standards including by taking into consideration the OSCE legal analysis of the draft law setting up this mechanism.

- Undertake Constitutional reform

– Undertake Constitutional reform to enshrine journalism as one of the pillars of a democratic society, with an explicit requirement of the State to guarantee it and protect it.

– Recognize the right to access information held by the State and public administration and the obligation of public authorities to provide such information.

– Provide all relevant state officials with training and support to promote and protect the spirit of such constitutional reforms.

- Foster an enabling environment for journalists

– High level officials should regularly communicate publicly, with a view to reaching a wide audience, that verbal attacks, threats, and hostility against the press should never in any way be tolerated; underscore the important role that journalists play in society and call for their full protection. Such statements could coincide with the celebration of international days, including World Press Freedom Day, as well as parliamentary debates, or public and official events.

– State officials and public figures should refrain from undermining or attacking the integrity of journalists and other media actors, or coercing or pressuring journalists.

– Provide journalists and other media actors who are victims of crime with quick access to preventive measures of protection, including court-issued protection orders and other personal protection measures taken by the police.

– Provide training for judges, prosecutors, lawyers, and police officers on relevant Council of Europe (and other relevant international) standards on freedom of expression and media freedom.

- Support female journalists

– Monitor and prioritize measures to protect female journalists against all forms of psychological pressure, intimidation, harassment, or physical threats, including as a result of online harassment, in line with the European Commission’s 2021 Journalist Safety Recommendation and the OSCE’s 2023 Guidelines for monitoring online violence against female journalists.

- End vexatious lawsuits, including SLAPPs

– Undertake further legislative reforms to address SLAPPs, in addition to the government’s recent transposition of the EU anti-SLAPP Directive, to extend judicial protection to domestic SLAPPs cases.

– Implement in full the European Commission’s Recommendation on SLAPPs as well as the Committee of Ministers Recommendation on SLAPPs; and, in doing so, extend Malta’s actions to both judicial reform and nonjudicial measures, such as victim support, judicial training, and public awareness.

– Reform the Media and Defamation Act to bring it in line with the recommendations included in the Legal Analysis of the OSCE Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media of November 2017.

- Strengthen access to information

– Take immediate steps to improve the swift delivery of information held by public authorities, and grant greater transparency with regards to the publication of official information in the public interest. Such improvements should be user friendly, efficient and embedded in a culture of accountability and openness.

– Disclose, in full, the legal advice received by the Government on the Freedom of Information Act, and undertake a full, transparent, and effective consultation for its reform.

- Build accountability by implementing the public inquiry recommendations

Ensure the full implementation of all the recommendations from the Daphne Caruana Galizia public inquiry, including those recommendations that relate to economic wrongdoing and financial crime, in their intersection of addressing the work of Maltese investigative journalists regarding state accountability, including:

- Amendments to criminal laws;

- Administrative practices which regulate relationships between public administration and business people;

- The fight against financial crime;

- Public officials who interfere with or attempt to interfere with the police;

- The introduction in the Criminal Code of the new criminal offence of “abuse of office” committed by a public official;

- The introduction into the Criminal Code of the criminal offence of obstruction of justice;

- The introduction of legal provisions in the Code of Ethics to counter inappropriate behavior by public officials.

- Ensure self-regulation contributes to safeguarding international standards

– Ensure that any changes to the regulatory ecosystem for media in Malta do not risk being misused for increased state interference. Self-regulation should be promoted and enabled by the authorities and all relevant stakeholders. Effective and independent systems of self-regulation must have the trust and confidence of the Maltese journalist community, and to the fullest extent possible, apply the European standards defined by the European Press Councils as part of the research and best practice developed by the European Union’s PressCouncils.eu project.

- Safeguard source confidentiality

– Develop protocols for law enforcement to embed the legal protection of legitimate and journalistic sources, including as part of investigations or operations. Such protocols should ensure that if investigative or intelligence collecting work by the Malta Security Service and or the police involves or touches upon the relationship of journalists and sources or whistleblowers, that the identity of that source or whistleblower will not be disclosed.

– The Protection of the Whistleblower Act must be reformed to provide whistleblowers with avenues for safe reporting, independent from government.

- Guarantee independent public service media

– In line with Article 5 of the EMFA, undertake reform of the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) to develop stronger institutional safeguards which protect it from all forms of political pressure and influence and increase its editorial independence, thus building public trust.

– Include transparent and democratic procedures for the election of all management staff and members to its oversight boards, to reduce potential political interference. Heads of public service media should in particular be required to adhere to transparent and impartial criteria in their appointment procedures, with a view to preventing undue political influence.

– Provide adequate, predictable and sustainable funding to the public broadcaster in order to create additional institutional barriers to prevent pressure from the government. Multiyear budgeting should be adopted to facilitate long-term strategic planning and enhance predictability.

- Ensure full transparency over the allocation of state advertising to media and establish an independent body to oversee this system

– In line with Article 25 of the EMFA, establish a registry for oversight of state advertising, which must be transparent, functional, and provide up-to-date and easily accessible data for journalists and citizens.

– Ensure this body is independent and issues annual reports on the distribution of funds, identifying any instances of preferential treatment or political influence.

– Award state advertising in accordance with transparent, objective, proportionate, and nondiscriminatory criteria. This should apply to allocation of advertising via public tenders, directly or indirectly, and via advertising agencies.

– Government agencies and state-run or -controlled companies should provide full transparency on advertising expenditure, while all media should disclose the total amount they receive from public funds.

- Increase transparency over media ownership

– In line with Article 6 of the EMFA, establish a national media ownership database which is public, transparent, up-to-date and easily accessible online. This centralized online registry should require data regarding the ownership structure, including both direct and nondirect ownership, as well as the identity of any beneficial owners.

– Document swiftly all acquisitions and mergers of media in the database. Noncompliance with requests for information on all aspects of ownership should be addressed through administrative measures or penalties.

- Prevent a high degree of concentration of ownership in the media sector

– In line with Article 22 of the EMFA, establish a coordinated system for the assessment of all new market developments that could lead to concentrations and have a significant impact on media pluralism and editorial independence.

– Adopt procedural rules to assess the impact of new acquisitions or mergers on media pluralism, as the Maltese media legislation does not contain specific thresholds or other limitations in order to prevent a high degree of horizontal and cross-media concentration of ownership in the media sector.

– Introduce measures that guarantee transparency and provide clear thresholds to prevent market concentration, including in the online environment.

– Designate an appropriate authority to monitor and measure media pluralism and to advise the competition authority in order to stop ownership changes that damage media pluralism and threaten editorial independence.

– Provide proper statistics on market shares and media revenues.

– Codify protections to journalists from political interference. Cooperate with the Institute of Maltese Journalists and other stakeholders to make sure protections are adequate.

This statement was coordinated by the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries.