Viorica Tătaru and Andrei Captarenco, journalism “Beyond the Dniester”

Viorica Tătaru and Andrei Captarenco, in their reports, describe the lives of Moldovans beyond the Dniester. In this interview, they explain the difficulties in describing daily life in a country divided between the territory controlled by Chișinău and that under the separatist government.

On paper a single and indivisible territory like all nations, the Republic of Moldova presents many internal differences and fractures. The most visible and acute, from a geographical and social perspective, is Transnistria: an unrecognized “state within a state” but de facto independent of the central power, born following an armed conflict (1992) that caused over a thousand victims.

Moldovan journalists Viorica Tătaru and Andrei Captarenco have been working for several years to tell the story of this region through the voices of ordinary people who find themselves, as the title of the program broadcast on TV8 suggests, “beyond the Nistru” (Dincolo de Nistru, while the Russian title is Reka bez granic, “river without borders” – the Nistru is, in fact, the river that marks the dividing line between the Moldovan territory controlled by Chisinau and the area controlled by the “separatist” government). We interviewed them.

How difficult is it to tell the story of Transnistria?

For us, it’s important to understand that “beyond the Nistru” live our fellow citizens, and what we aim to do with Dincolo de Nistru is to communicate with the people who live on that territory and who survived the 1992 war (which took place in that area and, thank God, never spread to other parts of the country). But, precisely, we start from the belief that Transnistria is part of the Republic of Moldova and we do not recognize the separatist government established in the region, just as we consider the presence of Russian forces in the area illegitimate (after the collapse of the Soviet Union, a contingent of the 14th Army remained under Moscow’s control, now known as the Operational Group of Russian Troops in Transnistria – GOTR, ed.).

Troops along the unofficial border almost always interfere with journalists from Moldova or, more generally, anyone who wants to travel to Transnistria with a video camera and microphone to document what’s happening. We’ve been stopped countless times, effectively illegally (because there’s no law enacted by a legitimate authority prohibiting us from carrying out our work in that territory), and the attempt is always to seize the filmed footage and testimonies collected. They don’t want the world to see the reality of the place.

Are the people you interview generally willing to talk?

Precisely because it’s so difficult to operate in Transnistria, and because it’s subject to constant scrutiny by local authorities, most journalists don’t go into the field. But for us, it’s an essential job: you can’t simply report the news without listening to what people feel and perceive in their daily lives. And if you stop at the first hurdle, then nothing is possible, and you might as well just sit in your office or in the newsroom with your hands tied.

That said, the people we interact with in the region are afraid to express themselves. Sure, they talk freely about their lives and occupations, but they rarely, if ever, criticize their government or the situation they find themselves in. On the other hand, it’s not normal that theoretically, according to the unofficial rules of local authorities, an ordinary citizen can only speak to you if you, as a journalist, have accreditation or a ministerial decision. This alone is indicative of the fact that people there are like in a huge open-air prison.

For us, voicing such a reality is also a way to raise awareness among Moldovan public opinion and the institutions themselves, so that the issue is resolved as quickly as possible. The current government and President Maia Sandu (who is pro-European, ed.) support our work, also because our perspectives coincide, but the central state has very little influence on the decisions made in Tiraspol (the self-proclaimed capital of Transnistria, ed.). Therefore, when we have problems with the separatist authorities, we still have to act alone.

In general, in Moldova, what are the biggest difficulties a journalist faces?

Right now, a major problem is represented by the opposition political forces, which are “fighting” the independent press. Unfortunately, many parties are simply repeating Russian propaganda, and – we can say this from our own experience – the majority of people who participate in their demonstrations and initiatives are paid for it. They receive money to go to rallies, their bus fare is paid, etc.

What happens? We go there and ask questions like “Why are you here?”, “What are your goals or political beliefs?”, and we get no answers because these are people, very often the older and less educated segment of the population, who aren’t participating spontaneously. So the attitude toward independent journalists is extremely aggressive, because for the opposition parties, it’s counterproductive to expose the reality of things.

We suffer attacks, we receive threats… Their goal is to discourage reporters from going to their demonstrations. And it can be a winning strategy: there are many young journalists in the newsrooms who want to do their job normally; they don’t think they have to go “to war” just to cover an election campaign. For us and others, it may be different: we’ve been in Ukraine, where war has been raging for three and a half years now, and we’re not intimidated and are fighting back. It’s important for us to expose the truth.

Anyway, with parliamentary elections looming, we know that attacks and threats are bound to intensify, just as Russian-inspired propaganda is bound to intensify. But, both as journalists and as citizens, we feel our duty at this time is to preserve social unity as much as possible, and we are confident in the path our country has taken, toward Europe and a future with greater protection of freedom of expression.

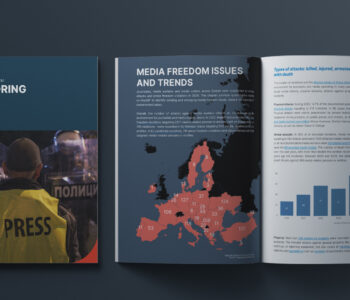

This statement was coordinated by the Media Freedom Rapid Response (MFRR), a Europe-wide mechanism which tracks, monitors and responds to violations of press and media freedom in EU Member States and Candidate Countries.